The drug trade has become increasingly deterritorialised thanks to a global network of dealers and traffickers who have taken their activity online, to a series of darknet marketplaces enabled by a combination of anonymous browsing, public-key algorithms, and cryptocurrencies.

“In an illegal marketplace you need to know the signs of the market, you need to be able to communicate with people and let them know that you’re a trustworthy buyer, that you’re not an informant for the police… and suburbanites who wanted to buy drugs would have to find a local to go to the marketplace and negotiate for them, usually in return for some of the drugs that were purchased.”

This quote from an interview with Eric Schneider, author of Smack: Heroin and the American City, illustrates how incredibly difficult it was to gain the “drug knowledge” needed to be a heroin user in postwar America without access to the kinds of places and people where heroin use was already happening. As Schneider explains, information such as where and how to purchase the drug, how to prepare it, what amount to ingest, and how to interpret the body’s reaction to it as pleasurable was “concentrated spatially and socially” in very specific locations.

It’s 2021, and this long-established geography no longer applies. Driven by the futile, decades-long War on Drugs, an increasingly more technically-sophisticated, impersonal, and decentralised global network of drug dealers and traffickers have taken their activity online, helped along by a combination of anonymous browsing, public-key algorithms, and cryptocurrencies. Now, someone who wants to use heroin can essentially get all the information and products they need from anywhere in the world, all that’s required is an internet connection and a postal address. Those three technologies give relatively risk-free access to one of several dozen darknet markets, commercial websites operating on darknets such as Tor or oI2P which sell, among other things, cyber-arms, weapons, counterfeit currency, stolen credit card details, but most of all drugs.

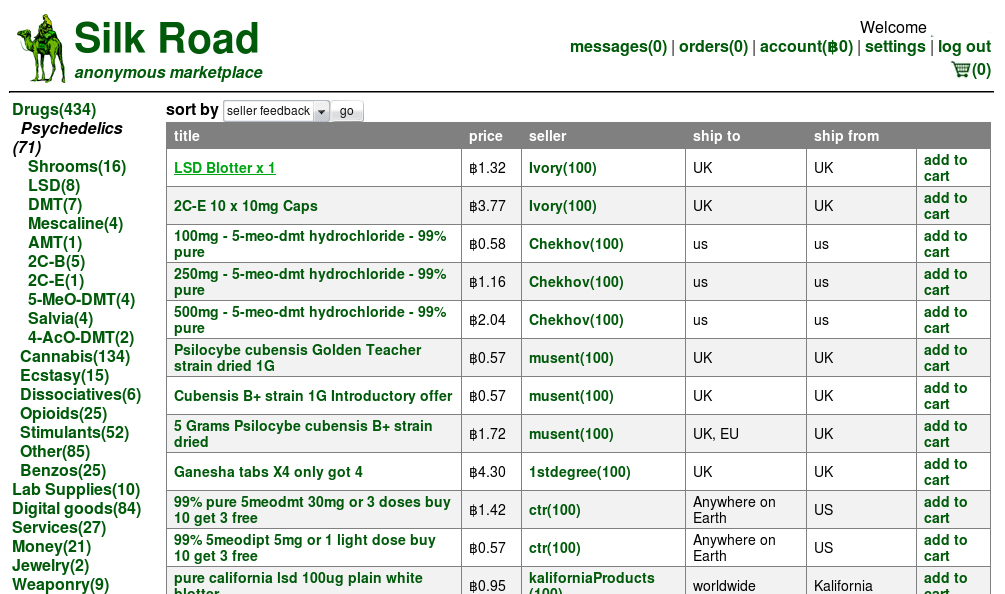

Until the launch of Silk Road, almost exactly a decade ago, this new online route to heroin and other illicit drugs didn’t exist. From February 2011, the site ran for two and a half years until it was shut down by the FBI. Since then, over 150 similar sites have emerged, few lasting more than a year. And while revenues are still minimal compared to the traditional offline drug trade, their persistent presence has had a hugely disproportionate impact on the geography of drug consumption. “Modern darknet markets have upended the traditional relationship between user and dealer,” says Mike Power, author of Drugs 2.0, “users can now choose from a plethora of options of suppliers from different countries. They can choose from different qualities. They can choose from different purities. And they can, in most cases, give fairly detailed customer feedback.”

ASTR0 BABY

What this means is that the darknet user can entirely insulate themselves from the process of drug production and supply through an online interface that is as dispassionate and impersonal as any other e-commerce website. For the darknet user, their drug consumption is now, more than ever before, displaced from its real-world ramifications.

In many ways, though, this isn’t so much a revolution as a culmination of a decades-long interaction between digital technology and the drug trade. As Power details in his book, drug users made use of the internet way before darknet markets came along. In fact, the first online transaction involved students at Stanford selling a bag of cannabis to a group of fellow students at MIT in the early 1970s. A couple of decades later, the proper online drugs scene emerged with the establishment in 1993 of the alt.drugs list on Usenet. Not long after that came Erowid in 1995, a website that hosts insights from users of psychoactive plants and chemicals, including Alexander Shulgin’s famous books PIHKAL and TIHKAL. Then, in the 2000s, the research chemical scene coalesced around message boards like Bluelight (est. 1997), where users share information and ask questions related to controlled drugs and harm reduction, among other things. With the advent of Web 2.0 came sites like Pillreports, offering detailed real-time user-generated information on ecstasy pills in different cities around the world. Pillreports was one of the first places to notice the MDMA drought of the late-2000s, which opened up an online market for the then-legal research chemical Mephedrone, a substance with similar effects to MDMA but different enough in its chemical form that it could temporarily evade existing drug laws. As Power writes in his book, “mephedrone was the first mass-market ‘downloadable’ drug, in the sense that it was, uniquely for the mass market, originally only available online. It was like a narcotic viral video, a digital diversion to be shared with the click of a mouse.” By the time the sale and possession of Mephedrone were criminalised in the EU in December 2010, the floodgates had opened for other research chemicals, similarly designed to exploit the near-endless loophole potential of chemical manipulation.

But while drug knowledge had already long-since drifted from the deep recesses of the city to the even deeper recesses of cyberspace, this drift remained a lateral one. The online drug scene may have been a less criminalised, less harmful and nerdier social space, but it was just as exclusive and its language just as niche and coded as the jazz and rock clubs Schneider references in his book. Besides that, it only expanded the kinds of drugs available, and until Mephedrone came along, only to a small group of people who knew where to look. By contrast, the character of new darknet drug markets has prompted a dramatic opening up of possibilities for where and what kind of drug use can happen. This is because now the codes concealing the transaction are not so much social as technological. No longer limited by the reach of their social network nor by their lack of access to drug knowledge, the darknet user is also privy to a level of information and choice that would have been scarcely believable a decade ago. Even well-known drugs like heroin, LSD and crystal meth were difficult to get hold of in many places before the 2010s. Now, however, a buyer can access these drugs from vendors operating on the other side of the world.

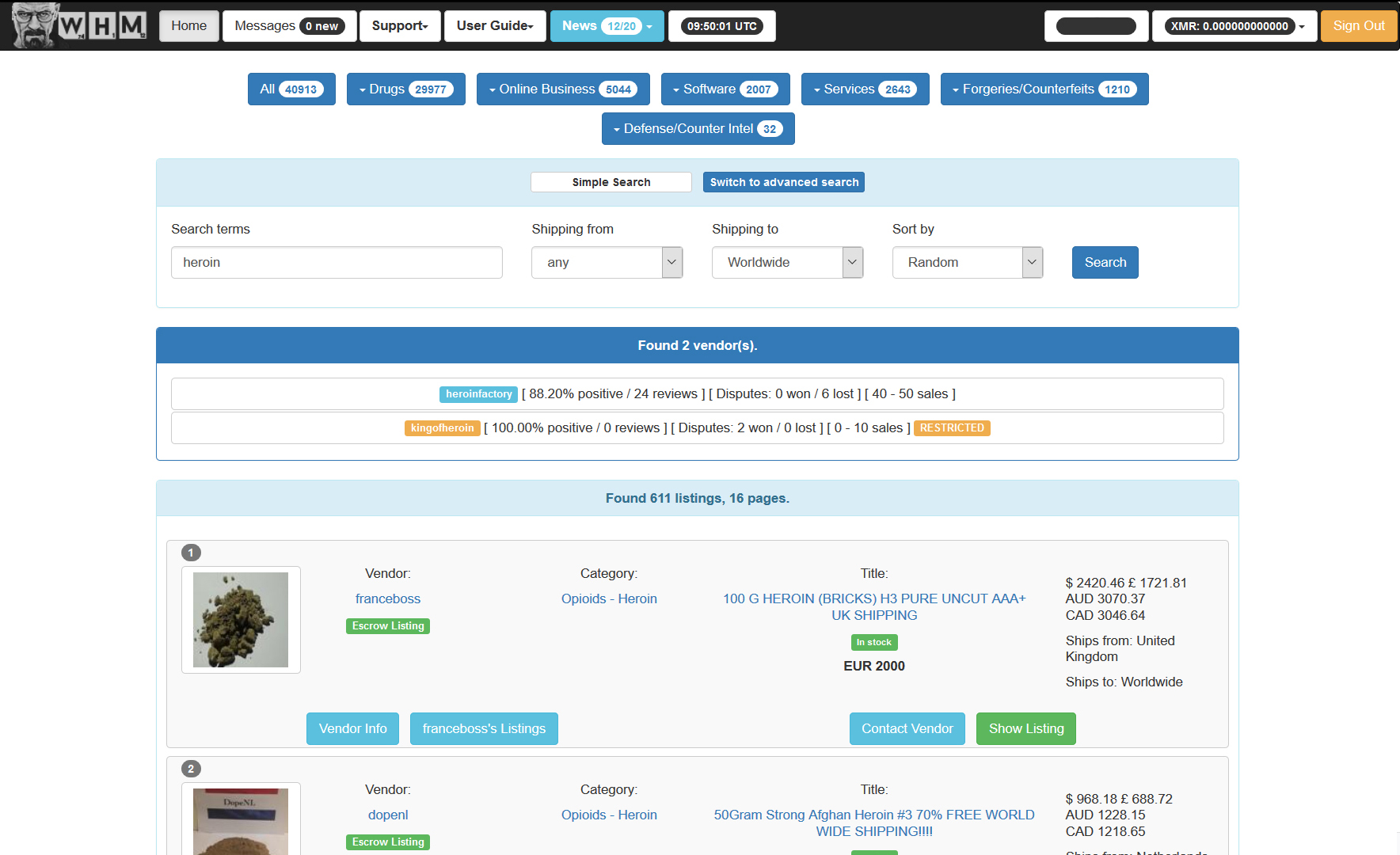

For instance, on White House, which emerged as the leading darknet marketplace in the second half of 2020, at the time of writing there are 1558 listings for LSD that offer worldwide shipping, while there are 611 listings for heroin and 142 for meth. Likewise, someone located in a remote part of the world looking to get their hands on even the most basic drugs previously had to pay a premium, take a trip to the city, or go without. Now, for the cost of international delivery, they can access the most obscure drugs imaginable. For instance, White House has 183 listings in the category “Psychedelics – Other” which ship worldwide, featuring a plethora of substances few people will have ever heard of.

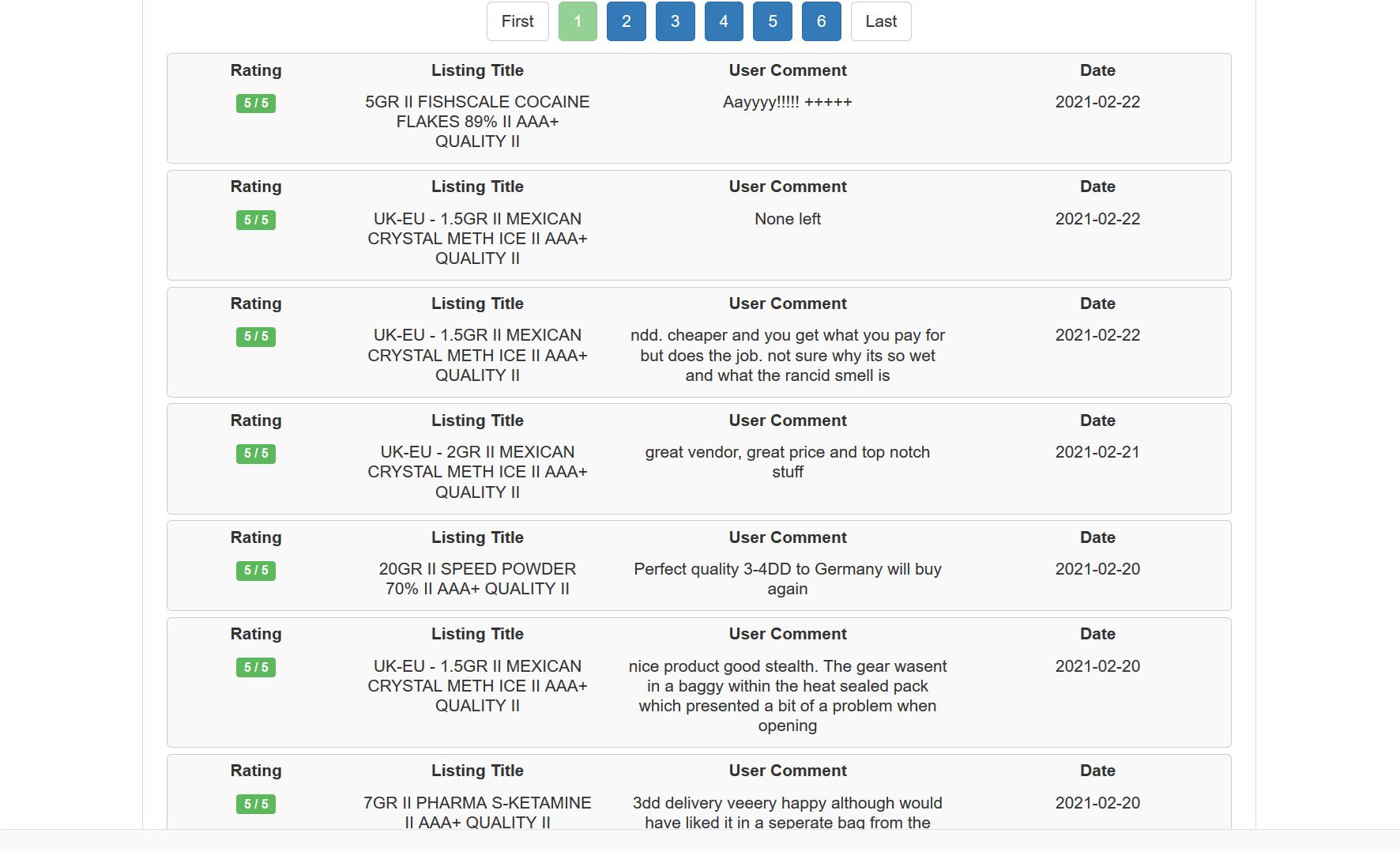

Thanks to systems of customer feedback that have the same disciplinary force on the retailer as we’ve become accustomed to in legitimate e-commerce, the darknet buyer can also reliably and safely get a measure of exactly what they’re buying. The purity of their drugs and the security of their package are easily attested to by previous buyers and by a simple rating system. Feedback for one major vendor on White House contains the kind of five-star reviews that, with a few omissions, wouldn’t be too out of place on Amazon Marketplace: “None left”, “great vendor, great price and top-notch stuff”; and on another top vendor “Excellent Trip !! Very recommended”, and “Took awhile to land but that’s not sellers fault. Product looks as advertised. Cant wait to try it!” [sic].

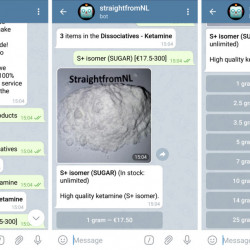

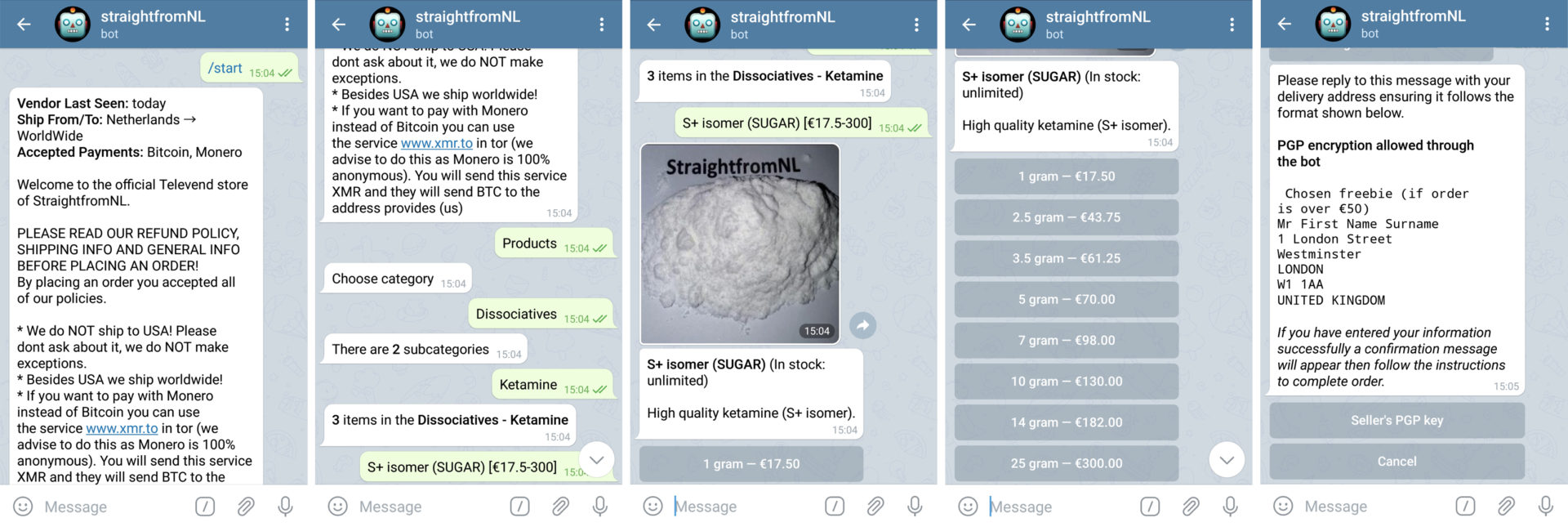

This kind of dispassionate, customer-feedback-enabled rigour has only become more pronounced with the recent arrival of Televend, a retail bot service operating on the messaging app Telegram.

Televend’s interface is so slick and impersonal that it’s quite easy to forget how astonishing it is: buying drugs from a chatbot on an encrypted messaging app on your smartphone, try explaining that to someone a couple of decades ago. “When I first saw Televend I thought “that’s it”, Power recalls. “Televend is the most incredible and most incredibly fast way of buying drugs I’ve ever seen. You’ve got this convenience, this ‘always available’ aspect.” After Power reported on Televend for Vice in October 2020, Telegram shut down most of the bots operating on there at the time. But, at least at the time of writing, it’s still pretty easy to find them.

Search “buy drugs” in the encrypted messenger’s search bar, proceed to the “buy drugs” chat and you’re offered a list of bot dealers, sorted by country, each offering a different array of products, but all roughly following the same format. The bot automatically sends a menu upon entering a chat, with the following message options: products, special offers, PGP (message encryption), terms and conditions, orders, feedback, payments, shopping cart, chat. Select products, and the drugs on offer are sorted by type: dissociatives, ecstasy, prescription drugs, psychedelics, stimulants, opiates. Choose, for instance, dissociatives, and then ketamine, on one bot, and it offers a choice of six quantity options, from 1 gram, at €17.50 through to 6 grams for €70 and 25 grams for €300. As well as the bulk-buy reductions, the bot advertises special offers for orders that go over a certain amount. After selecting the quantity of ketamine, the bot first asks for an address, which can (and should) be encrypted using the vendor’s PGP key, and then gives the vendor’s payment details (for transfer of Bitcoin or Monero). After that, all that remains is to wait for the package.

To summarise it like this, though, does overlook the many barriers to entry that make the whole process still mostly accessible to those in-the-know. Learning how to use the technology takes time, and the information isn’t that easy to find, which makes it all quite intimidating (if breaking the law wasn’t already). Until recently the source of a lot of how-to info could be easily found on the website DeepDotWeb as well as a series of subreddits dedicated to the dark web. But Reddit shut down these subreddits in March 2018, and in May 2019 a joint operation between the FBI and Europol seized the DeepDotWeb domain and arrested two suspected administrators of the site. It didn’t take long for the Dread message board to fill the void, but it’s only accessible through Tor browser, which also requires time to get accustomed to.

There’s also a lot the darknet user needs to get right to avoid revealing their identity. Bitcoin, which is already pretty arcane to most people, is not anonymous but pseudonymous (since the blockchain records every transaction and companies like Chainalysis can build up a detailed picture of a bitcoin user over time), hence the increasing popularity of Monero, which is much less traceable. Things are safer with PGP, which charmingly stands for “Pretty Good Privacy”. But PGP is also probably the most difficult thing to grasp. The technology essentially enables encrypted messaging through a public-key algorithm, whereby the sender encrypts a message with the public key of the intended recipient, which the recipient alone can then open with their private key. But while it would take an impossibly long time to decrypt the message without the key, problems in the implementation of PGP are well-documented. Moreover, the sender and receiver are also at the mercy of their domestic legal framework, which can be very draconian. In Britain, for instance, a suspected dealer can be given a 5-year prison sentence simply for not revealing their encryption key when asked by the police.

It’s also easy to get carried away and forget how small scale darknet markets are compared to the wider drug trade. Which drugs are bought and sold on the darknet also bears little resemblance to the overall share of the trade. Take for instance Empire darknet market, which was the largest darknet market before it disappeared earlier last year. It’s escrow wallets (i.e. the money the site temporarily held as a third party in every transaction that took place through the site) held $300 million, which represents two weeks of turnover, that’s $150 million turnover every week, or just over $20 million a day. This is trivial compared to the cocaine trade in London alone, which sells 23kg a day at a value of £2.75 million ($3.7 million).

As Power put it, “you’re always going to have a city banker, sat in a bar, on a Friday night with some disposable income, he wants to buy some cocaine, he will have it phoned-in and it will come to him by motorbike in 15 minutes if he’s in central London.”

This also goes for where that cocaine came from, which will remain, for the most part, Bolivia, Colombia, and to a lesser degree Ecuador.

But it’s the process in-between where the darknet has changed all of this. “The future of drug purchasing for many people, will only be online, I think it will only be digital, and that will change the spaces in which many drugs are bought and sold”, Power says. In a reflection of every other supply chain in the global economy “we’ve got smaller, more diffuse dealing organisations rather than massive cartels who just bring the cocaine in and then dump it on the streets of London. It’s a much more diffuse, distributed and scattergun, multi-target, multi-destination approach. You’ve just got more drugs being sold by more people in more ways than has ever been or was ever dreamed possible.”

In a scene from season three, episode one of The Wire, members of the Barksdale organisation gather together in a funeral parlour to debate the importance of territory for selling their product. Emboldened by the incarceration of his boss Avon Barksdale, the organisation’s second-in-command Stringer Bell is trying to apply the lessons he’s learned in his night school economics class to their criminal enterprise, but he struggles to convince his subordinates that good product eliminates the need to hold the best territory because the people will come to them.

At least in the short term, he’s proved wrong, and it contributes to the downfall of the Barksdale organisation. And he’s proved wrong because, ultimately, however good the product is, his organisation is still limited to the spaces where drug knowledge is concentrated, they still need territory and they need to put up with the risk that comes with it. These limits make Bell’s drug trade radically different from the markets he learns about in his economic class.

But modern darknet markets have the frightening potential to change all that, giving new space for traffickers to embrace the advantages afforded by modern commerce. Freed from the hard fight for territory, now they can unlock the power of retail and friendly competition, optimise supply chains, cut down on waste, exploit untapped markets elsewhere in the world, and make the whole transaction seem slicker, more reliable and less sordid, thereby shielding consumers from the often extremely violent conditions at the point of production and distribution. What’s more, they can do all this free from the nuisance of government regulation.

Darknet markets are one of the more extreme outcomes of the futile, decades-long game of cat and mouse, in which new barriers and punitive measures meant to stop drug traffickers, dealers and users have only encouraged them to find cleverer ways to keep buying and selling. In a gross abdication of authority, governments across the world have favoured prohibition and abstinence instead of regulation and harm reduction, putting power in the hands of people whose interest in the wellbeing of users and producers will never extend beyond the pursuit of profit. Drugs will always be around, people will never stop wanting to escape, get high, expand their minds or dull their senses. What can change is where this drug use happens, and where drugs are used, manufactured, transported, bought and sold. Until we all stop burying our heads in the sand and talk seriously about where we want this activity to happen, the worst people will remain in control.

*Cities After Algorithms

Cities After Algorithms is a content series exploring how algorithms generate and influence the spaces we live, work and move around in. Algorithms shape the city after their own image, but it is an image they have been trained to see. The tendency to mistake collected data for reality produces a self-fulfilling prophecy by leaving little room for intervention, experimentation or otherness. The more this technological determinism rules the use and design of cities, the more the city will be organised after mechanical parameters instead of socio-political ideals. The special series Cities After Algorithms is produced in collaboration with Failed Architecture, and is supported by the Dutch Creative Industries Fund.

Charlie Clemoes is a writer, editor and podcaster from the South West of England, currently living in Amsterdam. He is an editor at Failed Architecture, with whom he is currently producing the Failed Architecture podcast. He is also part of the Amsterdam-based design platform fanfare, principally as co-host of fanfare tetatet.